Victim

After dinner, John rested on the bed in his Dallas home, scrolling through his phone. Across the room, his girlfriend kept drinking. After four years together, John knew how to measure her mood by the liquid left in the bottle. It was November 2017, and the atmosphere in their house was particularly tense because their 16-month-old son was in the care of Child Protective Services (CPS).

She was a small woman, but when she drank she could fly into a rage. She didn’t like John spending time with his other kids from prior relationships. He had another woman’s name tattooed on his arm, a relic from a past romance. She especially hated that. She’d sliced up his forearm with a razor blade trying to cut it off his skin. Their neighbor, a mutual friend of the couple, was one of the few people who’d ever witnessed her dark side.

“John, don’t be naive,” she’d say, catching him when his girlfriend wasn’t around. “She’s going to kill you one day.”

On this particular November night, John was tired. They both had work in the morning.

“Hey, you’ve had enough for tonight,” he said without looking up from his phone.

She didn’t respond, and John glanced up just in time. She came down on him, his collectable Harley Davidson pocket knife clenched in her fist, and stabbed him in the gut.

She withdrew only to bring the knife down a second time, this time aiming for his heart. Former military training kicking in, John twisted and the blade sank into his shoulder instead. She then stabbed him one more time in the collarbone.

John’s vision began to cloud over after the second blow. But finally, a veil seemed to lift over his girlfriend’s eyes, as if realizing what she’d done. John begged her to call 911 and passed out.

Fighter

“I woke up to EMS reviving me,” John recalls three months later. He was lucky to wake up at all. A man of 36, with pink scars surrounding a name on his forearm, John is a guarded man in unfamiliar territory. In a former life, he was a sous chef in the kitchen of a high-end Dallas hotel. He had a girlfriend of four years. He isn’t perfect: John admits upfront that he has a record. He’s a survivor of family violence.

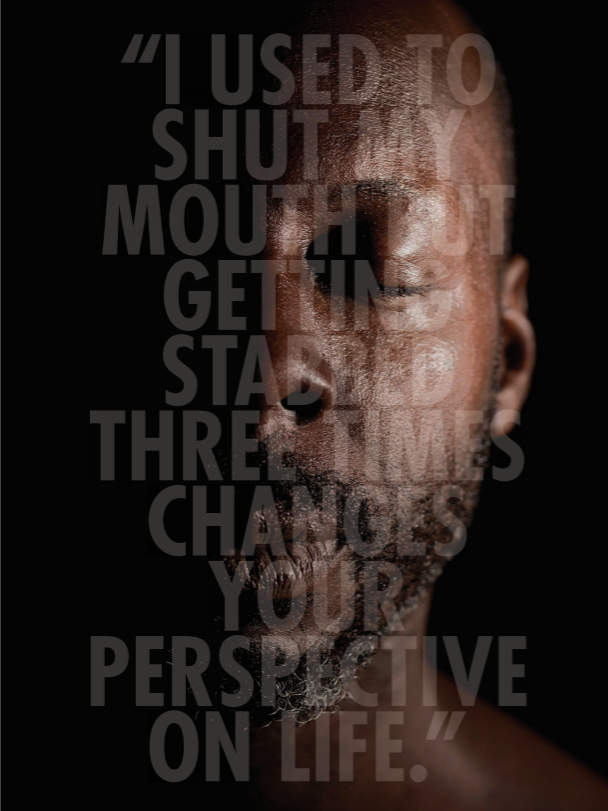

“I didn’t look at it as abuse,” he continues, telling his story with blunt, unflinching honesty. “I loved her. I used to shut my mouth, but getting stabbed three times changes your perspective on life.” He hasn’t seen his ex-girlfriend since that night. “I had a good job, a house, a life, a family, and because of this one person, I lost everything. Since then, I’ve just been trying to survive.”

According to a report on intimate partner violence and child maltreatment sponsored by the National Institute of Justice in 2006, nearly three in ten women and one in ten men in the U.S. have experienced rape, physical violence and/or stalking by a partner. In the U.S., one in four women and one in seven men, aged 18 and older, have been the victim of “severe physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime.”

John is a client of The Family Place, a Dallas nonprofit that specializes in helping people in the wake of family violence. In August 2016, The Family Place made national headlines by opening Texas’ first shelter for men who have been abused, one of a paltry handful in the country; there is one other shelter in Arkansas that takes in men. With space for 20 men, and their children if necessary, the new Family Place shelter is a quiet, comfortable, and a rare sanctuary for men like John. He’s one of the lucky ones.

Still in the care of CPS, John’s son is about to be returned to his ex. The day before John and I meet, he was told that he may lose his parental rights entirely.

“They look at me like I’m the bad guy,” he says. “They think I must have done something to her. But domestic violence can go both ways, you know? Men beat up women and sometimes women beat up men. I was laying in my bed, comfortable, feeling safe. She caught me at my most vulnerable. And I got stabbed three times.”

Despite the knife and a taped confession, the DA didn’t press charges. She served no jail time.

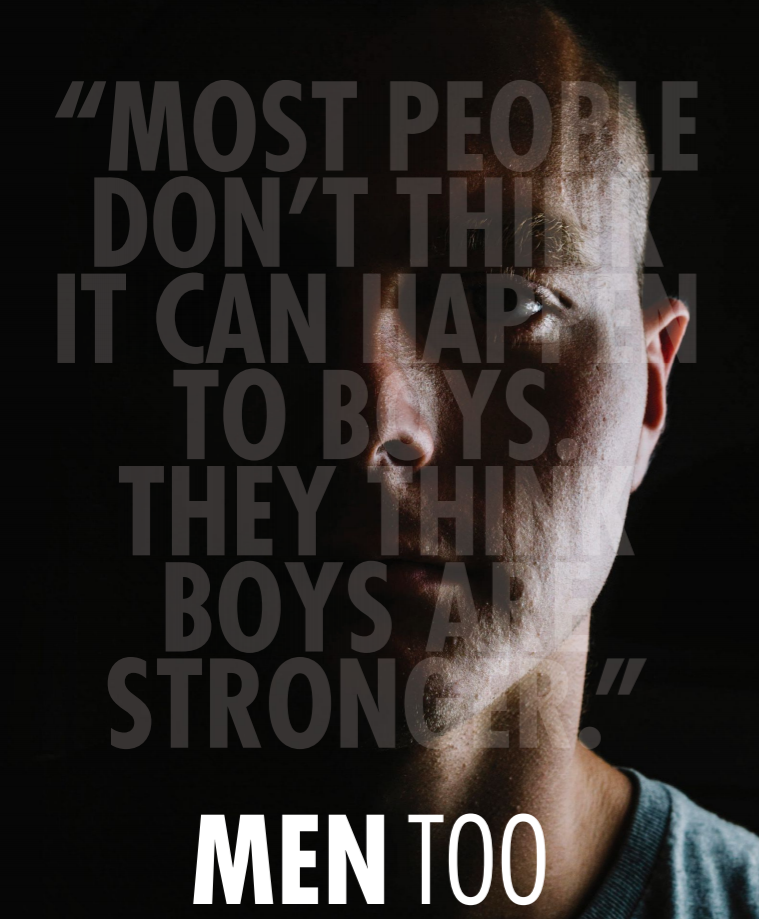

“People don’t believe this happens to guys,” he says. “Men have bravado. If it happens to them, they don’t want to admit to it.”

Paige Flink, CEO of The Family Place, knows stories like John’s all too well.

“While domestic violence does not discriminate when it comes to gender, many men remain silent because they think there’s no point in reporting the abuse,” she explains. “No one will ever believe them.” Open since ‘77, The Family Place has recently expanded. In addition to the men’s shelter, they also opened a second women’s shelter, more than doubling their capacity. Even with all the new space, they’re still turning people away.

Domestic violence is extremely isolating. Abusers keep power over their victims by separating them from others so friends can’t get close enough to see the bruises.

Out of the Shadows: The Texas Muslim Women’s Foundation

“[At the shelter] these survivors come together and realize they aren’t the only ones,” Paige says. “If you listen to these men talk about their experience, it’s just like what women go through,” she says. “Emotional abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse and physical abuse. It’s the same. People need to understand that anyone can be a victim. Asking for help is your right.”

Jim Malatich, CEO of Hope’s Door New Beginning Center, agrees. Hope’s Door New Beginning Center is a Plano-based nonprofit that specializes in comprehensive intervention and prevention services for anyone affected by intimate partner and family violence. “There’s no reason a man can’t be controlled or abused,” Jim asserts. “It doesn’t matter if you’re male or female.”

He explains that the difference begins when victims come forward. “If a woman is hurt, other women rally around her. Men laugh at men who get hit. So then they feel they need to man up.”

John lives at the shelter and works as a telemarketer while The Family Place provides legal aid. They’re transitioning him into an apartment in March.

“I love these guys,” he says when I ask about the staff and his housemates. “They made me realize I’m worth a lot more than I thought I was. They’re helping me every which way.” Though he admits having a curfew hurts his pride, John has much bigger problems to worry about. He has come away from his relationship with scars; the only women he trusts at this point are his caseworker and his mom. But most of all, he misses his son.

“I call him my chunky butt,” he says. “I love him. He is beautiful. He’s got a personality on him like you wouldn’t believe.”

Near the end of our conversation he pauses thoughtfully.

“Nobody wants to speak up for us,” he says. “The other guys here all asked me why I was talking to you in the first place. None of them want to go on record. But I want to speak for everyone. I almost lost my life. You have women abusers and men abusers. They come in every shape, size, form and fashion. You have to swallow your pride and admit what you’re going through. You won’t lose cool points as a man. You have to protect yourself.

“I don’t want to die.” He shakes his head. “Definitely not like that. So, I don’t care. I’ll put my name out there. It needs to be said, so I’ll say it. If it helps one person out there, it’s worth it. I’m a survivor.”

John offers advice to others in situations like his: “I’m a Taurus and I’m stubborn. I’m from Brooklyn. I’m an a******. If I can do this, as stubborn and hard-headed as I am, anybody can do it.”

Survivor

Male survivors of abuse often find themselves facing two kinds of shame; cruelty from their abuser and scorn from onlookers. When abuse escalates to sexual assault, the stigma can be even worse.

As Ken McGill, a psychotherapist in Plano, explains, “Every unfortunate experience is like a fingerprint. It causes a rupture in their ability to trust. Typically, boys aren’t socialized to identify feelings, much less report them. They keep it within and act out.”

Worse, Ken explains, that when it comes to sexual assault from a female perpetrator, some don’t even call that assault.

In November 2016, a female Plano ISD teacher was arrested for having an affair with her underage male student. While half of the public demanded she serve jail time, the other half scoffed. One Facebook commenter on a Dallas Morning News piece on the subject said, “What’s the big deal? Give the kid a high-five.”

However, Ken explains, even if it doesn’t look like abuse to you, that doesn’t mean it isn’t.

“Especially if they’re young—their minds are developing, their hearts and spirits are as tender as anyone else’s. They have a right to make choices about what to do with their sexuality and spirituality. The standard is yes, let’s prosecute if a man sexually abuses a woman, but let’s almost celebrate if a man is sexually abused by a woman.” Ken shrugs. “Which wound is deeper? The abuse or being brushed off?”

Ken suspects that there are far more men who are abused or assaulted than we know. Boys especially feel pressure to keep their emotions in check, to toughen up and protect themselves. When they are hurt, men and women alike frequently blame themselves. If there were more resources and greater awareness, there might be more survivors willing to come out of the woodwork. For example, in December 2016 The University of Texas at Austin estimated that of the 313,000 identified victims of human trafficking in Texas, 40 percent are male. They noted that male victims tend to be much harder to find and identify than their female counterparts.

In fact, Bob Williams, CEO of Denton’s nonprofit Ranch Hand Rescue was so shocked by the numbers, he decided to do something about it himself. A year ago, Bob sat in on a sex trafficking task force. It was the first time he’d ever heard about the prevalence of human trafficking in the country.

“Like most people, I was naive,” Bob says. “I was sitting in these meetings and one day I asked a question. I said, ‘Look, I get the need for shelters for women. But I haven’t heard anybody talk about men. What happens to them? Where do they go?’ And a [local judge] turned to me and said, ‘Bob, that is the single biggest problem we have in the country today. There are not enough beds for boys.’”

There’s a void for men who have been sex trafficked: minimal research, resources and programs. So Bob is opening his own shelter.

Ranch Hand Rescue is a jack-of-all-trades nonprofit. Bob started it as a farm animal sanctuary in 2008 and, over the years, has added special counselling services for veterans, abused children and anyone who didn’t respond to traditional therapy.

“Professionals and industry experts have helped us identify a need for a place for boys ages 18 to 24. If law enforcement can get them to safety, they have to have a safe place where they can heal,” he explains. This is a critical age. At 17, a minor who is sex-trafficked is automatically classified as a victim of child exploitation. But the moment that minor turns 18, they have to prove that they have acted under a trafficker’s duress or they will be charged with prostitution.

“We can’t find one long term facility for boys 18 to 24,” Bob explains. “We need better laws and more education for law enforcement. We need a sensitive police force. If they revictimize the male or assume he is the batterer, no one will ever come forward. We need to change our idea about these forms of abuse.”

“These kids [might be threatened]—if you don’t do what we tell you, we’re going to kill your mother, your father, your sister, your brother—or maybe they’re runaways picked up by traffickers. Maybe they’re kicked out of the house because they’re gay or transgender. These kids are innocent. It’s our moral obligation to do something about it. I never thought it would be me doing it,” he admits. “But I’m glad it is.”

Though there is much to learn about responding to women who have been assaulted, trafficked and abused, even less attention and credence is given to men in the same situations. There are barely any resources for male survivors, who reasonably account for 40 percent of victims.

“It’s much harder for men to come forward,” Bob says. “There’s a tremendous amount of shame associated with it. They think boys are stronger. They can defend themselves. In reality, they can’t. When you’re out there alone, beaten into submission, blackmailed, seduced—people don’t want to think about that tragedy. But they’re innocent. They didn’t ask for this. Everyone has a right to be free.”

Once the shelter is up and running, the survivors living there will join the huge community of people Bob helps. They could take care of the animals, which is an integral part of the healing process at Ranch Hand Rescue. He also plans to combine their veterans program with the safe house, allowing veterans to act as mentors for sex trafficking survivors.

Christopher Maples, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, runs the veterans programs. He himself has been diagnosed with severe PTSD and anxiety after discharge.

“I had a hard time connecting with people when I came here,” he says. “Over time, I saw clients, six-year-olds, 12-year-olds, connecting with animals. Then, a few months later, they’d be running around playing soccer with a counsellor. I saw their lives getting better. I thought to myself, these children were able to find their path back to life. If they can can do it, then I can too.”

Christopher is the first to admit that working with the animals is incredibly healing. “I’m always amazed at how animals who have been abused can rebuild humans. That animal is always there for you, regardless of what’s happened to you, because of what’s happened to them. Animals live in the moment. That helps us remember it’s okay to live in the moment. I can tell an animal everything before I can tell another person.”

Everyone who comes to Ranch Hand Rescue is coming out of hell. They arrive angry. Some children have been abused so badly, they don’t speak.

How Ranch Hand Rescue saves lives

“They have every right to be angry. They feel like they’ve lost their voice,” Bob says. And yet, working in the pasture with animals that trust and depend on them gives them a reason to come back. The animals have been hurt before; earning their trust is an honor. Ranch Hand Rescue fosters mutual relationships of caretaking, bonding and healing, from person to animal and person to person. When Bob started combining his human and animal programs, he had faith in their alchemy. He’d felt it himself. Bob is Ranch Hand Rescue’s first survivor.

“I was raped as a teenager,” Bob says. “I understand trauma and PTSD, shame and guilt. I couldn’t process what happened to me at 17. I can’t imagine a child trying to get through it.” He owns his own heartbreaking past peacefully.

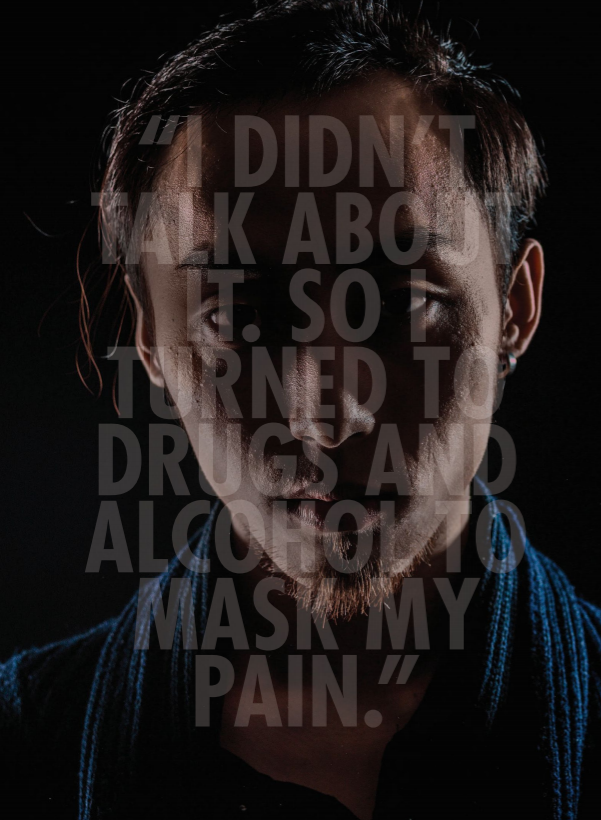

“I was beaten to a pulp. When my dad picked me up from the hospital, he said, ‘You’re going to man up, and we’re not going to talk about this again.’ The only people that ever knew about it where my parents and my family. In those days there wasn’t help for boys. I turned to drugs and alcohol to mask my pain,” Bob recalls. “I’m an addict. I’ve been clean and sober 31 years.”

Bob didn’t deal with his own trauma for ten years. Finally, he sought counselling, got clean and eventually opened his nonprofit. Ranch Hand Rescue is his purpose in life. He’s an example of a man living beyond his trauma.

“I designed this program for people like me,” he explains. “None of us asked for it. When I started this, I thought if I could save one animal, that would be great thing. Then when I added the counselling program, I thought if I could help one person, that would be great. I have the same attitude going into this safe house. If I can help one young man, that’s a great thing.”

Being a survivor is a weighty job. It’s an honor forged out of pain. There can be a powerful, redeeming bond between survivors of trauma, whether it’s two men sharing a safe house, or a veteran, an exploited child and a horse. Survivors understand the difficulty of surviving. They see that bad things can be done to anyone, stigma and stereotypes bedamned.

In the battle against pervasive wrongs like domestic abuse, human trafficking and sexual assault, survivors are frequently those who lead the charge. They may stay silent for years. But when survivors speak, we must listen. When they stand, we must stand with them.

Originally published in Plano Profile’s March 2018 issue under the title “Men Too”