I remember her eyeliner. I was thirteen and she was a friend of my mom’s, picking me up on a summery afternoon so I could babysit her two young boys. It was the last time we were ever in a car together.

“Do you like music?” she asked. U2 played faintly over the sound of the road and I said yes, I did like music. She was an erratic driver but she was so friendly I didn’t mind. Beverly Sliepka—Bev—had long blond hair and a huge, room-lighting smile, but my gaze kept straying back to her wobbly, uneven eyeliner. It looked like it’d taken a few tries and still wasn’t quite right. I wondered if she was aware of it.

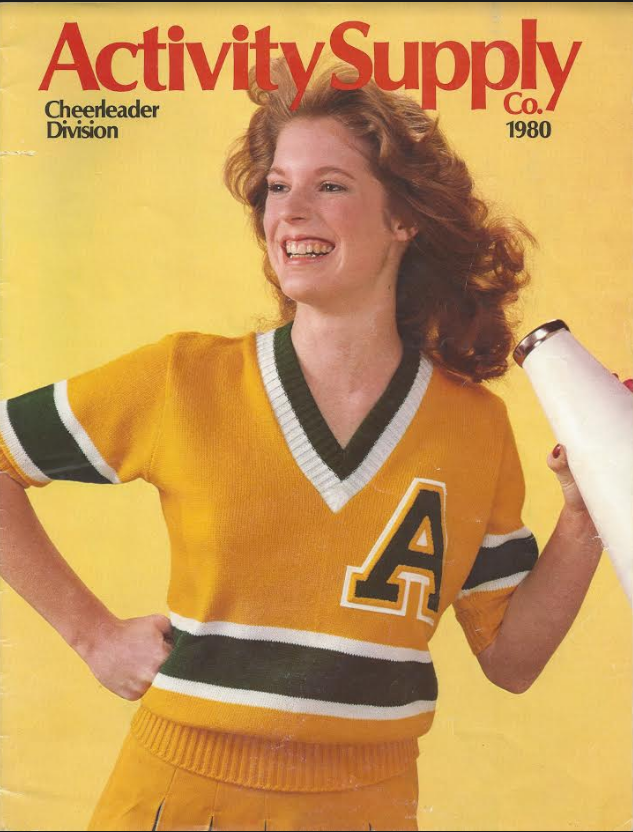

“She always struck me as so youthful,” one of her longtime friends, Sharon, said to me recently. She has trouble talking about Bev for long without tearing up. “A cheerleader type, full of energy. I always thought she had a charmed life. Looking at her wedding photos—beautiful bride, handsome groom, their nice house, two kids …

“I remember going on a road trip with her to the Hill Country. We stayed with her mom who was this quintessential Southern lady. She had doilies on all her tables. She and Bev were both so nice and so capable. I didn’t have to worry about anything,” Sharon said and paused. “Things couldn’t have changed more.”

“One time a group of us were taking a walk,” another friend, Helene, said. “I started to notice that when you were walking next to Bev, she would gradually run into you; she had a sideways step. Her balance was off. We all thought it was odd but didn’t worry about it too much.”

The first person to suggest that something was wrong was a cousin—a nurse—in town for a visit. He pointed out that when Bev walked, her feet turned oddly, one out to the side.

“I have no idea what it could be,” he admitted. “But I think you should see someone about it.”

Bev and Dave had a young baby, Payton, and were too preoccupied to dwell on what their cousin had said. It was only later that they began to see the signs themselves.

After the birth of their second child, Bev’s natural clumsiness went from harmless to pronounced. There was no question that something was wrong. In 2002, they went to see a neurologist. Bev had been adopted as a baby and never searched for her biological parents, so she had no genetic history. The neurologist had no logical starting point, so he began testing for one possibility at a time.

At first, he suspected MS. This was the first of what would be many tests for Bev. Tearfully, she and her husband prayed that the test would come back negative, and it did. Next they checked for Parkinson’s. Then brain cancer. Blood tests turned to CTs, MRIs and spinal taps.

“I can’t anymore, I quit,” Bev said a few times. “I can’t do more tests.” But the breaks from testing were never long. There was always a reason to go back.

“What are you looking for?” she’d ask the neurologist desperately.

He was very patient and in hindsight, wise. “I could tell you 20 things that it could be and you’d worry about 20 things,” he said. “If I tell you I’m testing for MS, you’ll worry about MS until we get the result. Then, if I tell you we’re testing for brain cancer, you’ll worry about that. I’d rather find out what it is and tell you when we find out.”

After four years of testing, Bev and Dave had a long list of what was not wrong. As symptoms worsened, they felt no closer to an explanation. She started experiencing sudden unexplainable bouts of irritability, her thoughts grew more scattered, and her legs began to spasm. Her neurologist gently suggested she stop driving. Bev abhorred the idea of being homebound, of losing her freedom, but after two minor car accidents—one with her little boys in the backseat—she gave up her keys.

In 2007, they finally got an answer. Their neurologist sat them down in his office and asked if they’d ever heard of Huntington’s Disease.

“No,” Dave replied, bewildered.

There was a brief pause. “We’re concerned that it’s Huntington’s,” the doctor said. Choosing his words cautiously, he explained that it was a genetic disorder and that they would need to test for the gene.

After Bev’s blood was taken for testing, Dave dropped her at home with a kiss and went back to the office. However, he couldn’t concentrate on sales. Instead, he typed “Huntington’s” into Google. The first result was a video of someone sitting in a wheelchair, unnaturally thin with jerky movements and slurred speech. Dave was chilled to the bone.

Later, the neurologist confirmed his suspicion. Bev had Huntington’s. Dave called his mother-in-law to tell her the news. He swears he’ll never forget the way she screamed into the phone. He realized then that Huntington’s wasn’t a diagnosis but a death sentence.

Huntington’s Disease causes the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain. It’s like getting ALS, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s simultaneously. It’s known as a family disease because every child of a parent with Huntington’s Disease has a 50 percent chance of carrying the faulty gene. Everyone who inherits the Huntington’s Disease gene will eventually develop the disease.

Today, there are approximately 30,000 symptomatic Americans and more than 200,000 at-risk of inheriting the disease. After the onset of symptoms—typically in their 40s—individuals with Huntington’s Disease face an average life expectancy of 20 years. Usually they die not from Huntington’s Disease itself, but from complications such as choking or infection.

For Bev, the primary horror wasn’t what lay in store for her but for her young children. Genetic testing for children of parents with Huntington’s Disease is typically prohibited until they are 18, unless they display symptoms of early onset. Her boys are both at risk.

Bev and Dave began learning everything they could about Huntington’s Disease, which is rare and notoriously difficult to diagnose. Doctors have to specifically test for it. It isn’t the sort of disease a doctor would stumble upon unless they expected to find it. It’s often misdiagnosed as lupus.

Bev and Dave also searched for her biological parents. While they never tracked down her birth father, they found information on her birth mother. She had died two years previously at a fairly young age. The cause of death was listed as lupus.

Ten years later

The Sliepka family resides in a two-story house in a quiet Plano neighborhood. Halloween is heavy in the air. Plastic pumpkins sit by the door and a gauzy ghost floats by the walkway. It’s one of the first chilly days of the year.

“Bev always loves decorating. She has stuff for every holiday,” Dave admits. “I hate decorating. I don’t mind once it’s up, but I hate doing it. But she’s sad if we don’t, so …” He waves at a cartoon witch dangling in the window and rushes back to the table; he’s in the middle of giving his wife of 21 years lunch.

A Dachshund mix vaults onto the high back of the couch and perches there like a squirrel, wagging his tail.

“That’s Cody. We’ve had him for three years,” Dave says, feeding Bev a bite of chicken and rice. “Bev, chew. We worried that the dog would get under her feet and she’d fall, but that hasn’t happened once. She calls him ‘her puppy.’ Bev, chew.” Dave helps her with the water glass she’s grasping for. “So, how did we meet, Bev?”

“Skiing,” Bev replies. “Colorado.” Bev’s blond hair is short and a little lighter now than it used to be. She’s looking forward to getting platinum highlights. Her movements are jerky and, these days, she’s confined to a wheelchair, but she’s very happy to have a visitor. While it’s admittedly hard for me to understand her slurred speech, Dave catches every word.

“We met in Steamboat Springs on a singles’ ski trip,” he adds. “We actually didn’t meet until the last night of the trip. I’m not saying it was love at first sight, but I knew right away there was something between us,” he says, feeding her another spoonful. “We got engaged a year to the day we met.”

A lot has changed since Bev’s diagnosis. Her two little boys are not-so-little; Payton is 17, and Zach is 13 and over 6-feet tall. After Huntington’s began to take hold, Bev’s mother moved into the house next door. She took care of Bev day in and day out while Dave worked. Earlier this year, however, she developed Parkinson’s and dementia, and now both she and Bev have caretakers. Still, whenever she comes over, she walks around primping the house and reminding the caretaker to make sure Bev has enough water.

“In Huntington’s Disease support group, we like to say ‘adjusting to the new normal,’” Dave says. “You go through stages of loss. I can’t tell you how many times we’ve said, ‘That’s the last time we’re going to the movies, or the last time we’re going to a Mavs’ game.’ Now a wheelchair is the new normal. So is having a paid caretaker.”

Bev and Dave are part of a small local community of people who have Huntington’s Disease, are at risk of having it, or know someone who has it. They participate in the annual Huntington’s Disease Walk and sometimes go to the monthly support group meetings, though Dave admits that’s hard.

“Most of the people are like me, caregivers. Some members have died. There’s one mother whose son died four years ago. Once I went and asked a woman where her husband was. They’d gotten a divorce. He couldn’t handle her diagnosis.”

For Dave, leaving Bev has never been an option. He says he’s never given it a thought. “I mean, what would I do, go try to live a better life? I’d just worry about her and the boys. That’s not better. I’ve seen it happen, but to me, it’s just not an option.”

As the disease takes its toll, their dynamic has shifted. These days, Dave and Bev more closely resemble a caregiver and a patient than a husband and wife. At a certain point, Dave recalls she stopped asking about him, about work, about how he felt.

In his efforts to keep his wife out of a facility—a future that grows closer every day—he has given up privacy, ease and income. When their paid caregivers clock out for the day, he’s afraid to leave Bev alone long enough to go to the bathroom. He works from home as a sports collectibles consultant.

Money is tight. Because Bev was diagnosed in her 40s, years before most people even consider taking out long-term disability insurance, they don’t have that crucial coverage for Bev’s care.

Though it goes against his nature to ask for help, last year Dave reluctantly set up a GoFundMe page with a $50,000 goal—gofundme.com/BevsCare. Donations have trickled in and, while they are nowhere near their goal, every penny has helped.

It’s been a ten-year-long, slow grieving process with only one outcome. “But you never really know [about life],” Dave says. “After we found out Bev’s diagnosis, I told my buddy, Brad. He and his wife were going to come over to support us and bring us a meal. The very next Friday, he calls me. His wife had died of a brain hemorrhage out of nowhere. Instantly it went from him helping me to me helping him.”

That friend recently remarried. He and Dave talk sometimes about who had it worse. While Brad had no warning or chance to say goodbye, Dave has felt himself losing Bev for a decade.

“It used to make me angry thinking about retirement, travel, grandkids, all this stuff that we wouldn’t have—but she’s still here. Not all of her, but parts of her,” he says. He hasn’t ever been able to decide which situation is better.

As time has gone on, friends have come and gone. Even some of their closest friends have let them down.

Bev and Dave have a Care Calendar where neighbors sign up to bring meals. At first, friends dropped off Frito pie, meatball soup and chicken spaghetti every week, but their visits have tapered off over time.

“I’ve had people come back to me trying to explain that they stayed away because they didn’t know what to say,” Dave explains. “But even if you just say that, that’s sharing your heart. You don’t have magic words; I don’t have magic words. You can’t fix this. Don’t pretend you can.”

Dave pauses to make sure Bev has her drink. “People want to grieve, get closure and go on, but Huntington’s doesn’t work like that. It lingers. People don’t know how to say they’re sorry for 10 years.”

While Bev can still live at home, she can’t be unsupervised. She’ll choke on air, or on her own saliva, not to mention the danger of eating and drinking. She lacks the impulse control to keep herself from standing up, or doing other things that could hurt her. If she chokes on a piece of food, her body doesn’t know to stop and cough; she’ll keep trying to eat. She needs to be walked through something she’s done every day of her life.

Someday, Bev will need full time care in an assisted living situation. She recently spent one week in a facility while Dave took his sons on a trip to see family. It was incredibly difficult.

“She kept begging me not to leave her,” Dave says. “I’d been looking forward to being away with the boys, and I thought it would be okay. But when I dropped her off, I was crying. Even the next day on the road, I was crying. I missed her so much. It was so hard.”

As Huntington’s Disease has taken its toll, Bev’s awareness of her disease has perhaps abated. Her irritability symptoms have faded and some of the tics that developed in the early stages of her disorder have calmed as her muscles deteriorate. She’s adjusting to life in a wheelchair.

“For a while she was angry and bitter,” Dave admits. “Huntington’s Disease also made her irritable, and I’d have to remind myself, ‘That’s the disease talking, not Bev.’ But that phase is gone. Now she’s just sweet and that’s what I loved about her when I met her.”

Huntington’s Disease won’t be around forever. Doctors know the exact gene that causes it and say it’s not a matter of if there will be a cure, but when. Huntington’s Disease is so rare and awareness so low that a cure isn’t a priority for drug companies. They would rather focus on cures that would affect 30 million people, not 30,000. However, knowing that a cure will come gives families with Huntington’s Disease in their DNA hope.

A little more of Bev’s mind and body escape her every day, but her long term memory is surprisingly good. She’ll mention that she used to work with DJ Kidd Kraddick in KISS-FM’s sales department and once got to meet Tina Turner. If you bring up her love of music, she’ll tell Dave to get the picture she took with the Goo Goo Dolls six years ago. Bev loves talking about her sons. She’ll tell you about the sports Zach plays, Payton’s new job and how proud she is of them.

“We were worried she’d lose her personality and memory but the sweetest parts of her have stayed,” her old friend Jenny says. “When you’re with her, you catch little flickers of her, like glimpses of light.”

Her friend Helene says that whenever she goes by for a visit, Bev remembers that she writes music and has two daughters and tells her so. “Your daughters are beautiful,” she repeats over and over.

“That’s Bev’s way of giving, remembering something that’s important to you,” Helene says. “She’ll keep saying the same things, but it’s always complimentary.”

Beverly Sliepka is ten years down a road she never wanted to travel. Though her body and mind are slowly waging war against her, and she won’t live to see a cure, Bev is still fighting. She isn’t out of love to give and she still finds a way to let you know she’s happy to see you. When you visit, she remembers who you are, what’s important to you and what you mean to her. Perhaps that’s the way she would like to be remembered.

Before publishing this piece, I sent it to Dave just in case I missed some crucial details. He returned my email with one last thought about Bev.

“I never mentioned her smile and her ‘explosive’ laugh,” he said. “You hear it less and less every day, but when you do, it’s worth everything. If you aren’t in the room when she’s laughing, you run in there just to be around her. Those moments are less common, but they’re live-giving. They’re reminders of better days.”

——–